In 2016, NHS England claimed in their personalised medicine strategy,

“if we get our approach right, the NHS will become the first health service in the world to truly embrace personalised medicine. We will create a healthcare system focused on improving health, not just treating illness, able to accurately predict disease and tailor treatments” (NHS England 2016).

Recognising that personalisation was happening across multiple domains, not just healthcare and medicine, our collaborative project has asked how personalisation affects our concepts of the person, and what the consequences are for health and well-being. As the project ends, we briefly look back at the past four and a half years.

The phrase and title of our project, ‘People Like You’, refers to an address and an invitation, for example in a recommendation to buy something (‘people like you buy things like this’). It implies that you are one of a group or category sharing something in common, and therefore you (singular and plural) might welcome this recommendation. We suggest that ‘People Like You’ encapsulates a wider framing of recommendations than the online shopping and browsing that we all know so well. ‘People Like You’ are recommended tailored health treatments and prevention messages, public services, including personalised social care budgets, and social movements (via hashtags inviting ‘likes’, sharing and affiliation).

In a recent book, Michael Schrage situates current algorithmic methods in a longer history of what he calls recommendation engines, for example through divination or astrology, and provides details of current methods using case studies such as Facebook (Schrage 2020),

“Recommendation inspires innovation: that serendipitous suggestion—that surprise—not only changes how you see the world, it transforms how you see—and understand—yourself. Successful recommenders promote discovery of the world and one’s self…Recommenders aren’t just about what we might want to buy; they’re about who we might want to become.” (see too Rieder’s Engines of Order, 2020)

Our project team includes anthropologists, sociologists, clinical scientists, and creative practitioners. We have worked on case studies to explore how personalisation happens, and focused on three interconnected Ps which we consider common to personalisation across different sectors: Participation that also allows for the tracking of personal data; Precision in the making of categories of person based on similarities, differences, and preferences; and Prediction (or Prescription) in making these categories relevant and actionable for a variety of purposes.

Our empirical studies have included breast cancer medicine and care, HIV research, digital culture and algorithmic identities, and data science in health studies. Halfway through the project we were disrupted by the pandemic and shifted our collaboration online. Fieldwork for some case studies had to be suspended, and one of us (HW) was re-deployed to the Imperial COVID-19 Response Team. Working on this major health problem created new opportunities to study practices relevant to personalisation (see blogs on lockdown in Italy, the 2 metre rule, shielding, two-by-two, and COVID-19 categories).

Three artists completed residencies: Di Sherlock’s held conversations in our research sites of personalised cancer medicine and care from which she crafted poems (Written Portraits); Felicity Allen explored questions of representation and ideas of the self associated with digital culture (Dialogic portraits); Stephanie Posavec explored data science and personalisation in a large health research project, Airwave (Data Murmurations: points in flight).

What have we gleaned from our four-and-a-half-years’ collaboration? Our website documents activities and events, case studies, outputs, artwork, and emerging insights in our blog. In this final reflection we offer a few examples of themes spanning this wide range of work.

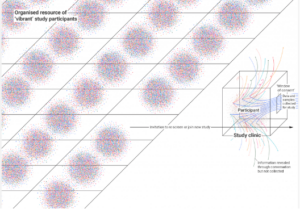

The relationship of persons and data has been a consistent theme. Stef Posavec explored this explicitly in her residence with the Airwave study, “how is the original donating person (participant) figured at every step of the collection and research process?” Stef figured participants as ‘data point clouds’, explaining in one of her talks, “we are all a cloud of data points that are just waiting, latent within us, to be activated through data collection”.

Stef shows how data points are selected and organised in the process of data collection and draws attention to those that are not collected, during conversations with research nurses, for example; they are “lost… (data) points bouncing away like the particle trails and quantum physics experiments”. One of her informants, a data manager, likened unstructured data in the system to “blobs of binary”.

Felicity Allen also reflected on how a person might be figured in a portrait in the form of a painting, a poem or a data set. As she explained, “In this project I’ve often thought of the brushstroke as a form of data which builds a picture of a person… So what type of brushstroke most resembles data, and whose data is it, the sitter’s or mine?”

This relation between the person and their representation in data or art was tackled explicitly in Di Sherlock’s Written Portraits residency. Di talked about sitters and their response to the poems she created; “the poems were negotiated and edited until they were considered to fit, that is, to constitute a resemblance or likeness that both sitters and poet liked.” This speaks directly to two aspects of liking – similarity and preference – which we have proposed as key elements to personalisation.

We asked about these and other ways of figuring persons in a conference at the end of 2019, Figurations: Persons In/Out of Data. Some of the key papers from this meeting will be published this summer 2022 by Palgrave Macmillan. The collection and other work we have done asks who has the power and capacity to develop personalised services, products and offers. Despite contrasting perspectives from personalising practices in different sectors, our public event in September 2021 agreed that personalisation can deepen inequalities and exclusion. In medicine, translational research that underpins personalisation is based on large collections of data and biological specimens which accumulate in the process of clinical studies. Many groups are underrepresented in these resources because of unequal Participation, and so recommendations emerging from the findings are not necessarily relevant or appropriate. Findings from biobanking are also relevant to the knowledge and recommendations constructed in relation to COVID-19.

Flick explained how, “Working with ‘People Like You’ extended my thinking, from power relations imbued in the individual gaze of a privileged artist, to connect this to the intransigent and godlike oversight industrialised as surveillance. It led me to think that the failures to adequately represent through portraiture may possibly be analogous with the failures to adequately predict through data”. The tension between potentially useful personalisation, where services and medicines may be tailored to the needs of an individual, and potentially damaging surveillance is visible across our work.

Grouping ‘people like you’ based on patterns in data (by preference, similarity, proximity) can be very Precise and can remain Precise as data sets grow, are linked and statistical computing power increases. Categories of ‘People Like You’ can be very granular and reflect an almost real-time grouping and regrouping of people, underpinning recommendation algorithms in many sectors. But they do not necessarily enable accurate Prediction. Acting on a pattern to target an advert may not seem particularly sinister but it has been shown that vulnerable groups receive damaging, and do not receive relevant, recommendations. In medicine, detecting patterns of ‘People Like You’ at group level and using them to prescribe, or proscribe, for individuals is challenging, and in healthcare at least we should be wary of using algorithms to automate decisions.

These are just some of the themes of the project….and an overview of our approach to the 3Ps of Personalisation is in press with Distinktion. We will post a link on this website to Personalisation: A new political arithmetic? when available; it will be part of the special issue emerging from our 2021 workshop – People Like You: A New Political Arithmetic.