At the time of writing, the 2020 London Marathon had not yet been called off because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nor was the sitter a professor: he was awarded a Chair subsequently in 2020 for his work in epigenetics. Epigenetics means ‘above’ or ‘on top of’ genetics. It refers to processes that modify gene expression but do not change the DNA sequence. Most definitions stipulate that these modifications are heritable (see Vital Conversation).

“I’ve had three lives already,”

he says

fixing me a macchiato freddo.

Coming from “a long tradition of baristas”

he makes a professional brew

despite the modest machine –

a far cry from the bar in Rimini

where his first life began

twirling the baton bestowed

by his Great Grandmother

amongst the fashionistas of the day.

“My hobby was Uni in Bologna.”

He’d have preferred to study architecture

but his mother vetoes the choice,

declaring for medicine –

a nurse herself.

Sadly for her it’s the year

of Dolly the Sheep

and he opts for genetic engineering.

Riding the wave of R&D

provoked by the EU ban on antibiotics,

he writes his thesis on pig nutrition.

His second life is spent

in the realm of Animal Science and

cowboy hats –

Purdue University, Indiana,

where the crew of Apollo 11

chewed the cud later digested

in Zero G.

Its the back of beyond.

But once he’d left

he decides

“it was not a bad place to be”

and returns.

Come mai?

He flashes a Mastroianni grin.

And so

he sashays back to Purdue

and four years of Epigenetics

with a sideline teaching tango

to students and seniors –

milonga not Strictly.

He does a post doc in Michigan –

“scientifically a waste of time” –

as subprime mortgages

leave Lehman Brothers bancarotta.

His third life begins in New Hampshire –

“a bubble of rich hippies.”

He meets his half Sicilian

but “very British” wife

in the Dartmouth Medical School Building

by the ice machine

getting ice for their experiments.

Ten years later, back for a seminar,

he photographs the iconic machine.

“Life histories start always from

the weirdest of places.”

She’s an exchange student

in need of a room,

he has a house.

Ecco fatto!

“First she lodged in my house then in my life,”

he laughs.

Well, not entirely –

first he had to convince her

he wasn’t gay.

He relates this in full lycra –

a sporty invitation to camp.

“It’s the look!” he protests.

“Perception and reality are not the same thing.”

He’s in training for the London Marathon

never run before

though kicks a football.

Beneath the lycra

tattoos lurk.

A lizard-like creature mounts a forearm.

Inked in Indiana

it’s a “doodle” of his own design.

It echoes the aboriginal art of Australia –

a place he might have lived

if it weren’t for arachnophobia

and the offer of London.

On his other forearm

the daughter of Alphonse Mucha gazes

sybil-like.

Draping his left shoulder

Klimt’s Hygeia.

On his back Hokusai’s Wave,

The Fighting Temeraire on his chest.

Terror from behind,

the final port of call ahead –

the body speaks prophetic

to the first time Marathon runner.

In the cramped office

a supersize computer screen surfaces

like a giant turtle,

in back a sticker:

I am a DAD.

His son’s photo is on the wall

under the fauve swirls

from his niece’s paintbrush.

He’s a happy boy,

who can strum Wimoweh on his ukulele –

a mini-me version of Dad’s guitar.

Together they watch Ted cartoons –

Schrödinger’s Cat no challenge

for the quantum world of a two year old.

“It doesn’t matter

what he does as long as he thinks critically,”

he declares.

Then, hearing himself, grimaces

as if Il Dottore had appeared on the scene.

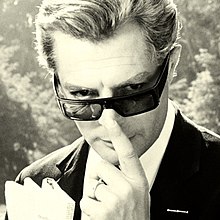

Behind the elegant horn rims

the eyes dance.

The professorial beard

is “the lazy man’s answer to shaving.”

But without the beard,

he reflects,

he’d “feel like a bartender again.”

After six years at Hammersmith Hospital

his fourth life –

Research Professor –

is upon him.

Best not shave.