A few weeks ago, jobs were trending on Twitter. On October 6th, the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, dodged a question on TV about what people in creative or event-based industries ought to do for work. These industries have been heavily affected by COVID-19 lockdowns, leading to widespread job losses. His response, that “everyone is having to find ways to adapt and adjust to the new reality,” strongly implied that these workers were going to have to learn to do a different job. He also said that the government had “put a lot of resource into trying to create new opportunities.” So, Twitter users decided to check these resources out.

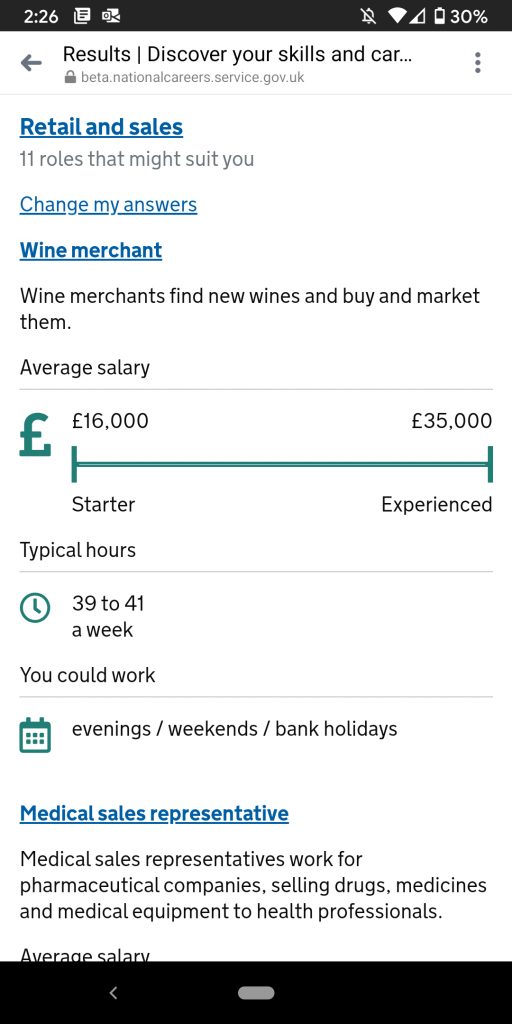

What they found was a questionnaire on the National Careers Service called Discover Your Skills and Careers (DYSAC). This questionnaire was designed to help people figure out what kind of work they might be suited for. Jobs started trending because some of the results of this test were bizarre, in poor taste, or seemed to ignore the damage done by COVID-19. I was told I’d make a good wine merchant, which I though was funny—I like wine—but also not a career one can just pick up. Other users, including one of our PLY colleagues, reported being advised to take up careers in boxing, which is hardly the most sustainable work going. Most egregiously, perhaps, some were told they’d be best suited to work as actors or entertainers—the very careers Sunak was warning that people might have to leave.

The reasons why this DYSAC questionnaire made headlines are pretty obvious. If we peel back the angst and irony that made this questionnaire into a trending topic on Twitter, though, we can use the DYSAC to illustrate what we mean by personalisation—and why it sometimes falls well short of what it promises.

The DYSAC questionnaire is a part of a branch of psychology called psychometrics. Psychometrics quantifies human attributes—like intelligence, aptitude, behaviour, or emotions—to make them measurable and comparable, using instruments like questionnaires or tests. The IQ test is probably the most infamous historical example, but psychometrics are also widely used by big organisations. These tests are supposed to reveal things about you that can’t be gleaned from a job interview, like whether you’ll be suited to a particular role.

To create the DYSAC, the National Careers Service contracted SHL, one of the biggest global providers of psychometric tests that measure aptitude for jobs. SHL are famous for their Occupational Personality Questionnaire (also known as OPQ32), which is designed to predict if a prospective employee is likely to perform well by measuring 32 personality characteristics divided in to three major areas, “relationships with people,” “thinking style,” and “feelings and emotions.” Are you controlling or outspoken? Conventional or adaptable? Worrying or optimistic? The idea is to quantify these characteristics and map them on to roles that require particular personality types.

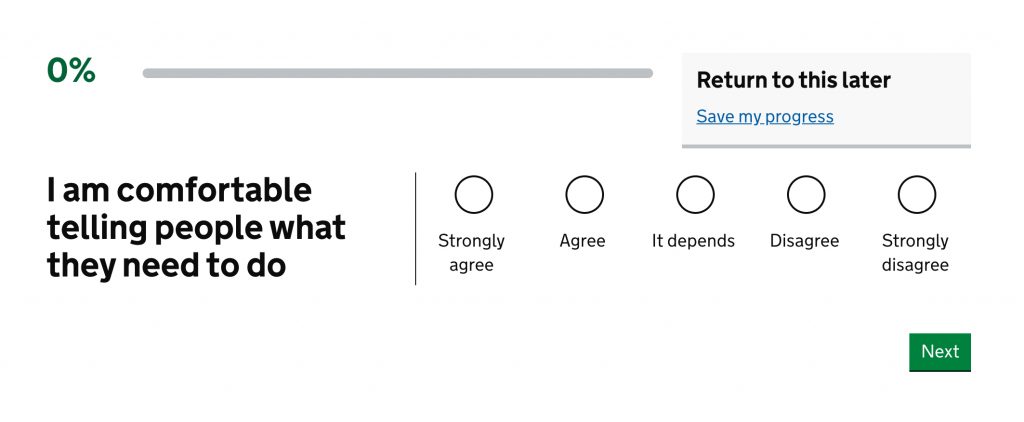

The DYSAC is a bespoke—and much more simple—version of this test. It’s a “normative” test, asking respondents to rate how strongly they agree or disagree with a particular statement on a “Likert-type” scale of 1-5. But it also reverses the psychometric principles that underpin the OQP32. Instead of using psychometrics to find the best person for a job, the DYSAC determines a person’s behavioural styles to find out which jobs they might fit. On their company blog, SHL Senior Consultant Helen Farrell describes the brief they were given like this: the National Careers Service “wanted to be able to empower the user to explore potential career paths they might have not have otherwise thought of.” This aspiration is noble enough, but it’s also the source of the ensuing controversy.

The DYSAC assumes that self-knowledge will help one succeed at work. What’s interesting to us is how it does this: it attempts to address you. That is, its series of questions generate results that say this is you. This mode of address is the source of Twitter’s ironic response to the questionnaire, because many people felt like it didn’t address them at all. The problem is that its results feel anything but personal(ised).

Psychometrics employs a peculiarly modern technique: it attempts to quantify a trait—in this case, personality—to make people comparable and classifiable. Much of the controversy surrounding the DYSAC stemmed from a feeling that its advice was generic. People reacted to what they saw as the test’s inability to comprehend their personal context or the broader context of a post-COVID-19 world. People simply couldn’t relate to some of its results, and they definitely didn’t want to be told they had an aptitude for a job in an industry that the pandemic had shut down.

This controversy also stemmed from the way it presented data about prospective jobs. There are a lot of websites out there that give advice about how a prospective employee ought to approach the OPQ32. One of the disclaimers these websites like to make about it is that “there is no wrong kind of personality.” But the panel of results generated by the DYSAC, its simpler sibling, make something else abundantly clear: some personality types seem to be much better remunerated than others. The DYSAC revealed much about how we are valued as people.

But this controversy also arguably stemmed from the test’s failure to produce a personalised outcome. This is what makes the experience of doing the DYSAC test feel so utterly strange. It reduces self-knowledge to the occupation one ought to aspire to. In order to understand you, instruments like psychometrics have to understand you as a type. Only, what’s being optimised isn’t the type of job for the person, but the type of person for the job.

Thought it might have failed to present a personalised outcome, the DYSAC nevertheless illustrates a few of the paradoxes of personalisation that we’re so interested in. Personalisation can only address you as a person by understanding you as part of a collective. The DYSAC fails because it doesn’t manage to sort the person back out of the collective its questions sort them in to. And yet it also demonstrates the strange flexibility and reversibility of the category of this “person.”

One of the phrases that we find ourselves returning to time and again is one that often accompanies algorithmic recommendations: “people like you like things like this.” The DYSAC applies an inverse logic. Their results are based on the proposition that jobs like this like people like you. Personalisation can mean personalising a job for a person, but it can also mean personalising a person for a job—in this case, by trying to quantify personality traits that match best to a role reduced to a type.

When personalisation works, this backwards logic just feels right. When it fails, well, it just feels wrong. I’m not likely to try to be a winemaker anytime soon. But besides having a job, I’m in a better position than an artist friend who received the result below after doing the DYSAC test. Perhaps the problem with the government’s failed attempt to personalise job advice is that too many people felt like the DYSAC didn’t “recommend any job categories” to them. People like them, it seems, aren’t liked by jobs at all.